Why you're better at whistling than singing

Published: May 2, 2018

As far as mammals go, we humans are pretty good at using our voices. We sing, talk, lie ŌĆō and imply ŌĆō with the subtle dips and rises of our voices.

We learn to use our voices by imitating the sounds that we hear, this is part of how infants learn to speak.

Speaking even has a kind of sing-song element known as tone of voice that allows us to emphasize some words over others, ask questions or express emotions. So you might expect that humans should be expert singers.

We are, so far as we know, the only ape that sings. But that also makes us the only ape to sing poorly.

And it turns out, weŌĆÖre better at whistling a tune than singing one.

Off key

Even opera singers, who are probably about as good at singing as humans can be, are sometimes off the mark.

Unlike the voice, most instruments have a set of keys, holes or buttons that let it make a fixed set of sounds. If the instrument is well-tuned, all of those sounds will be notes in a musical scale.

Other instruments like the violin or trombone make a continuous range of sounds, just like the voice. They can also sound off key, by making the same kind of mistakes as a singer does.

Still, it turns out that . That is, singers are more likely to miss their note than violinists, for example.

ThatŌĆÖs a bleak outlook for Homo vocal virtuoso, but is this really a fair competition?

Violins and trombones are built for the express purpose of making musical sounds. With an appropriately tuned instrument, placing a bow over the strings in a certain way ought to be pretty consistent in the sound that it makes.

Should we really expect the same thing from the voice?

The human kazoo

The pitch of your voice comes from your larynx (sometimes called the voice box). ItŌĆÖs a collection of cartilage, muscle and membrane that sits in your throat, conveniently located between your lungs and mouth.

When air passes between a pair of membranes in the larynx, they vibrate like a comb and wax-paper kazoo. Just like the kazoo, when these membranes are stretched, they make a higher pitch, and when they are relaxed, they make a lower pitch.

Try holding your AdamŌĆÖs apple and saying ŌĆ£zzzzz.ŌĆØ Did you feel something? To make the ŌĆ£sssssŌĆØ sound you swing these membranes out of the way so they donŌĆÖt vibrate any more. Try it, no more vibration, right?

But the voice has a disadvantage. The larynx is controlled by a complicated and interconnected set of muscles. Whether one muscle raises or lowers the pitch of your voice can depend on what the other muscles are doing.

Also, these are muscles! They get tired if you use them too much. They change as we grow, learn and age.

Instruments, on the other hand, are professional tools that get regular tuning.

Lips versus larynx

To , we compared it to whistling instead of instruments.

Just like singing, whistling makes a continuous range of pitches by passing air over a quivering mass of cells, except that when we whistle, we trade larynx for lips.

In the lab, we had people listen to simple melodies then try to sing or whistle the melodies back. We compared the pitches of target notes with the pitches that people actually sang or whistled.

Humans spend hours each day controlling the pitch of their voices ŌĆö conveying love, sadness and anger. Despite all this practice, people were closer to the target note when they were whistling.

Even in a fair contest, the voice didnŌĆÖt measure up.

Studies of , and communication have showed that apes can do more with their voices than you might think, but they donŌĆÖt come close to the skill and variety of the human voice.

This tells us that the human skill with the voice evolved after our ancestors split from other apes. These studies also tell us that control over the lips evolved much earlier, and we think that this might explain our findings.

Maybe evolution hasnŌĆÖt had enough time to tune the larynx. It could also be that the larynx is tuned just well enough for speech and for many of us, singing just asks a little too much.

Whistled speech

If we have this long-since evolved skill with the lips, then why donŌĆÖt we speak in whistles?

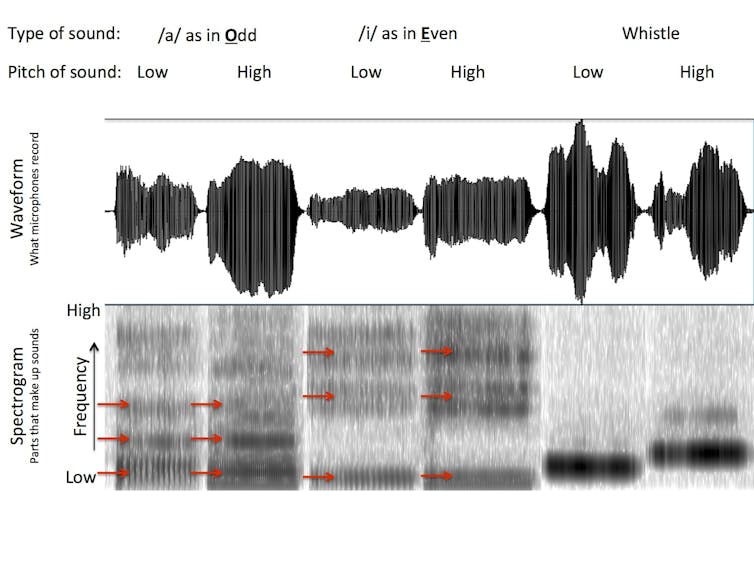

The answer is that the voice carries a lot more information than just high and low pitches. We use the placement of our lips and tongue to amplify some parts of our voice and dampen others. This is how we build up the sounds that we use to speak.

Whistles on the other hand are very simple sounds, and there is not much room for the rich acoustic tapestry of speech.

However, some people have found a way to whistle their languages, such as in the mountains of the , the , ŌĆö and maybe even in .

Whistles may carry less information than the voice, but they will carry much further. That can be handy when your friends are out of earshot ŌĆö or rather voice-shot.

, Postdoctoral researcher at ; of ; and , chair professor of

This article was originally published on . Read the .

![]()